|

| Surf workouts |

So how generally to optimise strength/fitness? What do I know already? I've learned along the way to fuel before & after exercise, and my dad, once ripped back in the 70s, suggested to us as boys that pushing to the limits was good, and on strength building 3 sets of 8 was the way to go then to up the weight when it became too easy. My triathlon buddies seem to blend interval and slow-paced runs into their endurance training. My electrophysiologist buddy Marie suggested pushing to failure on the last set. Let's see what a bit of research has to say about getting stronger and getting fitter...

General principles of strength and fitness building

Accepted advantages of exercise: energy, mood, sporting ability, improved sleep, stress tolerance, attractiveness, libido & sexual prowess (whoop!), alertness, weight management, improved immunity, chronic disease avoidance. Strength & bulk-wise: some say this confers a perception of authoritativeness, and you might imagine some occasional practical application (lifting fallen trees from crushed cars is a rarity, though...)

Tips on exercise motivation: ideally be doing an activity that you intrinsically love, vary the monotony of training formats, capitalise on supportive friends&family, make a plan, reward yourself, find a role model, develop your background knowledge, set goals, measure your performance against those goals, train socially. Sounds reasonable enough.Nutrition - quantity:

The body uses the same energy molecular currency 'ATP' everywhere. This is the end product of breakdown of carbohydrates, proteins, fats. Adequate protein levels are necessary for tissue repair and muscle building, and fats are important for vitamin absorption and hormone production.

During intense training periods, increased intake is recommended:

1.3-1.8g protein/Kg/day (that'd be 104-144g for me, = 4 tins tuna or 4 chicken breasts or 20 eggs!) (Phillips & Van Loon, 2011)

30-60 kcal/Kg, that'd be 2400-4800kcal for me, of which 30kcal/Kg should be carbs. (Tarnopolsky, 2008)

Lots of water, even better if this replaces electrolytes too post-exercise, particularly sodium.

Nutrition - timing (I've used weak sources here, but I've found consistent guidance)

3-4 days before endurance event: carb-load with 12g/Kg/day of low-GI foods (e.g. seeds, wholegrains) prior to an event to maximise glycogen stores

3 hours before race: eat a small meal (400kcal) to allow insulin to normalise

In the last 3 hours pre-event: keep drinking about a pint of water an hour

Immediately before exercise: top-up a few mins before with a carb snack with a little protein

During exercise: Isotonic carb drinks/snacks during exercise (i.e. take an energy bar to the beach). If exercise lasts >2 hours, incorporate some protein into the fuel during the exercise to avoid muscle catabolism.

Recovery: carb (1.5g/Kg in first 30 mins after exercise) w/ protein snack (~40g) post-exercise

There's no evidence that splitting the diet into more than 3 meals a day makes a difference - many researchers have looked into this (Helms et al., 2014)

During intense training periods, increased intake is recommended:

1.3-1.8g protein/Kg/day (that'd be 104-144g for me, = 4 tins tuna or 4 chicken breasts or 20 eggs!) (Phillips & Van Loon, 2011)

30-60 kcal/Kg, that'd be 2400-4800kcal for me, of which 30kcal/Kg should be carbs. (Tarnopolsky, 2008)

Lots of water, even better if this replaces electrolytes too post-exercise, particularly sodium.

Nutrition - timing (I've used weak sources here, but I've found consistent guidance)

3-4 days before endurance event: carb-load with 12g/Kg/day of low-GI foods (e.g. seeds, wholegrains) prior to an event to maximise glycogen stores

3 hours before race: eat a small meal (400kcal) to allow insulin to normalise

In the last 3 hours pre-event: keep drinking about a pint of water an hour

Immediately before exercise: top-up a few mins before with a carb snack with a little protein

During exercise: Isotonic carb drinks/snacks during exercise (i.e. take an energy bar to the beach). If exercise lasts >2 hours, incorporate some protein into the fuel during the exercise to avoid muscle catabolism.

Recovery: carb (1.5g/Kg in first 30 mins after exercise) w/ protein snack (~40g) post-exercise

There's no evidence that splitting the diet into more than 3 meals a day makes a difference - many researchers have looked into this (Helms et al., 2014)

Getting stronger - and building muscle

Strength and power:Simply, strength = ability to lift things (force). Power = ability to lift them fast (force x velocity).

Weight training also offers a choice between strength increase and hypertrophy (muscle size) - it is possible to prioritise the look rather than the functional ability. Functional goals first seem more my kind of principle...

Frequency of exercise:

Reps: 1-5 strength; 5-8 muscle hypertrophy & strength equally, 8-10 hypertrophy; 12+ endurance (meathead wisdom, supported by Mangine et al., 2015)

Sets: 2-3 for strength, this is 45% more effective than just 1 set. (Krieger, 2009)

Rest: 5mins for strength; 30-60secs for hypertrophy (one study suggests 3mins); 20-60secs for endurance (de Salles et al., 2009)

Sessions: 3x per week is optimal for beginners to avoid mental fatigue, leaving at least 48h between the same exercise, and at least 1 full day off a week (therefore maximum 6x training per week)

Vary your training across the week: using one day in the week to focus on each of strength, power and hypertrophy is best - thanks Rob for the intro to Daily Undulating Periodisation (Rhea et al., 2002)

Features of the exercise (more meathead wisdom):

- Compound exercises are most time-efficient (rather than isolating a specific muscle and working it, which means much more time in the gym would be required)

- Free weights use more muscles than resistance machines - you use the stabilisation muscles too

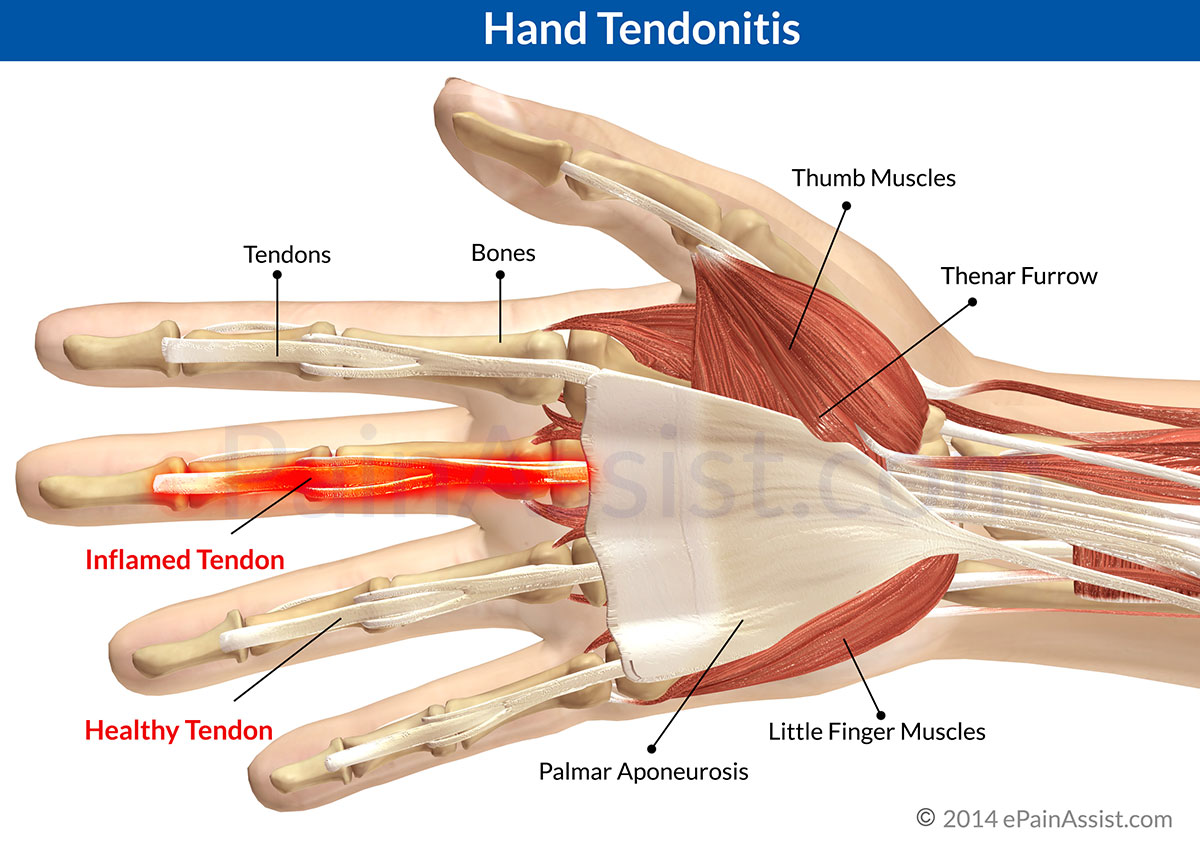

- Injury avoidance - proper form when lifting reduces injury risks, and barbells are best to avoid injuring yourself

- Training to failure (i.e. until you can't do any more reps): this is exhausting, and may affect the rest of a workout leading to less overall work done, aka 'central fatigue'. That said, the intensity may increase strength gains for the target muscle. So - use it with consideration!

- Specific exercises: squat and benchpress at least twice per week

- Endurance training decreases strength training performance - so cut the long runs if you're looking simply to strengthen up

Getting fitter and faster

What is fitness? (US Surgeon General, 1996, Ch3 p.72)(1) Cardiovascular capacity (heart contractility, left ventricle dilation, stroke volume)

(2) Skeletal muscle adaptations (increase in number of mitochondria in muscle, more oxidative enzymes within mitochondria, better capillarisation, faster diffusion of oxygen and fuel into muscle, increase of fatigue-resistant slow-twitch muscle fibres)

General tips on building fitness

|A| A regular training stimulus is required for adaptation to occur and be maintained

- adaptation: (1) after a power sprint session - 2 days; (2) after a VO2 max oxygen debt, e.g. hills session - 2 weeks; (3) after a long endurance session - 6 weeks.

- detraining: this is significant within 2-4 weeks. Fitness can be maintained despite a 70% reduction in training frequency/duration, as long as the intensity of that training is maintained, but if not then all functional gains are lost after 2-8 months (US Surgeon General, 1996, Ch3 p.72)

- generally start with higher volume & low intensity, and adapt to lower volume & high intensity as competition approaches

- 'periodise' into four week blocks, and make a focus out of each of the four-week blocks, e.g. strength, speed, power, technique, endurance or post-race active rest (Bazyler et al., 2015)

- focus on skill acquisition in periods of lower training volume & intensity

- taper off before competition (for 1-4 weeks, depending on how rapidly you detrain)

- vary the intensity of training. One coach recommends that 10% of your training should be faster than your race pace, i.e. if your 5km run pace is 6m15 miles, do 80% at 8min miles, 10% at 7min miles, 8% at 6min miles and 2% at 5min miles. This 80:20 split of higher to lower intensity training is accepted wisdom for runners and other endurance athletes (Seiler & Tonnessen, 2009)

- incorporate muscle-work: when strength training is the focus, use the gym. High-force, low-velocity training at 80% of your 1 repetition maximum for 5 or 6 repetitions on relevant muscle groups yields the best results (even tho' lots of people don't like the gym!) (Bazyler et al., 2015)

- have a calmer week every fourth week or so - helps you recover and stay fresh & keen

- high intensity interval training (HIIT) incorporates short periods (e.g. 30s-5m) of maximal effort followed by a rest, preferably of active recovery. There's no clear optimal level of the work:rest interval, but 1:2, 1:1, 2:1 are frequently mentioned, confers endurance benefits up to 2x per week (Seiler & Tonnessen, 2009)

So what about the surfing?

What's needed:

- strength and endurance: bursts to catch the waves, endurance to paddle all day, balance and power to pop-up on uneven waves

Use a surfing-specific training manual to make the plan:

- Nutrition: pre-load with lots of high GI carbs, carb/protein snacks, energy drink, carb/protein recovery drinks

- Warmup: follow the 7 surfing-specific dynamic routines

- Swim (in the pool): interval training combining high intensity burst swimming (30-60s) with endurance work.

- Strength @ home: HIIT the pull ups, push-ups, lunges, squats

- Gym (1): full body/balance - deadlifts, overhead presses, single-leg squats/medicine ball tosses,

- Gym (2): core - medicine ball / stability ball

- Gym (3): shoulders&back - cable chops, bent rows, cable pulldowns etc.

- Stretching: best done post-exercise

And what next...

So food's in the bag, exercise is in the mind (!), now for tagines, freshly caught fish, and NYE beach party...

|

| Local transport here we come |

Review credit - thanks to Rob Armstrong, including his important caveat that although general principles apply, everyone is genetically different, one size does not fit all, so you have to try things out to see what works for you.